A few days ago, while scrolling through Instagram, I came across the existence and work of blablalab.eu. It’s a collective that works on initiatives to promote awareness and action around Climate Change.

One of the things I found most interesting about blablalab’s approach is how they understand people in a complex way. That is, they don’t think there are “the smart ones” who care about climate change and “the dumb ones” who don’t get it. Instead, they acknowledge that society is much more complex. Based on research, they’ve tried to map out the reality of society regarding climate change by identifying eight profiles that describe eight major groups into which Spanish society can be divided based on their relationship with the issue.

You can check them all out here:

https://blablalab.eu/presentacion-de-los-segmentos/

Well, as I was going through that, I kept thinking about how simplification (the idea that “those who believe what I do are the smart ones, and the rest are dumb, old-fashioned, backwards…”) is at the root of the absurd polarization we see in almost every part of our society today. I notice it particularly these days when there’s a lot of noise around “revisiting” digital technology in schools.

So I thought: one of the things we really need to get clear is that society is complex, and as blablalab shows so well in the context of climate change, when we implement things like digital competence in education, the goal isn’t to get “the smart ones” or “the ones who think like me” on board… What we need is for everyone to be committed to Digital Competence. That is, if we understand it as a basic and fundamental literacy, then to achieve it, the messages and initiatives we launch within institutions must consider the diversity of the people involved. We must not direct generic messages to “everyone,” but rather try to tailor messages to specific audiences.

This has been echoing in my mind especially during this time when governments are making public statements about removing screens from schools “to save the children”… while doing very little to go beyond generic headlines or one-size-fits-all policies.

So what now? Well, I thought I should do something within my own sphere of influence, and the most immediate one is my students. I want to work with them on understanding the importance of recognizing that families (and each person within a family) hold diverse perspectives, and that teachers must engage critically with students’ digital competence from those particular viewpoints.

So, we’re going to do an activity based on those perspectives. To do that, I’ve been thinking about what those family profiles might look like. Ideally, we’d have good research to base those profiles on, but since we don’t, I’ve been working with ChatGPT and DeepSeek to create a set of hypothetical profiles for the task with my students — and here’s what came out of that.

Mapping Family Perspectives on Educational Technology

In 21st-century classrooms, educators encounter a complex mosaic of family perceptions about the role of screens in learning. Far from a one-size-fits-all stance, these views are shaped into six archetypes that interact—and sometimes clash—within the educational space. Understanding their nuances is essential to building effective communication bridges.

1. The Guardians of the Analog

They represent a conscious resistance to digitalization. Their discourse, woven with concerns about neurodevelopment and platform capitalism, questions the very foundations of educational technology. In their homes, physical books and unstructured play are sacred. To them, each screen in the classroom is a dangerous concession to the fragmented attention model of the digital era. Their greatest fear: that schools will normalize what they see as a “loss of essential childhood.”

2. The Tech Evangelists

At the opposite end of the spectrum, these families see every device as a gateway to the future. Their belief in innovation often outweighs scientific evidence: they assume early exposure to digital tools guarantees competitive advantages. Their homes are laboratories of educational apps, and they push for schools to accelerate their digital transformation. Paradoxically, their enthusiasm can verge on uncritical, equating novelty with pedagogical progress.

3. The Weary Navigators

They embody a lived contradiction: aware of the risks yet surrendering to daily realities. Their rules are flexible, driven more by exhaustion than conviction. Screens serve as parental anaesthesia during endless workdays. At school, they support any use of technology that lightens the domestic load, though they suspect they should be stricter. Their unspoken motto: “The lesser evil in a lost battle.”

4. The Nostalgic Rebuilders

Their stance is a mix of longing and activism. They constantly compare today’s childhood with their idealized memories of streets, notebooks, and unsupervised games. Screens, in their view, steal essential formative experiences. While not outright rejecting tech, they create “technology-free zones” at home and look skeptically at digital whiteboards. Their uncomfortable question: Are we medicalizing childhood by pathologizing its disconnection from the digital?

5. The Late Navigators

This group embodies the digital divide from a systemic perspective. Their relationship with educational technology follows a slower adoption curve shaped by structural factors (unequal access, limited digital literacy, or language barriers). Unlike ideological resisters, they want to participate but find digital ecosystems unintuitive. Their deepest frustration: feeling like they’re always “trying to catch a train that’s already left,” especially when schools assume a baseline of digital competence. Educators must build bridges without assuming prior knowledge.

6. The Informed Dialectics

Their position is built on constant questioning. They reject both moral panic and tech fetishism, demanding nuance: YouTube is not GeoGebra, just as a textbook is not a novel. Their key value is pedagogical intentionality. They’re the ones who ask in meetings: “What specific problem does this tool solve?” and “Do we have data on its real effects?”

IMPORTANT: The Connective Tissue

These profiles are not rigid categories but dynamic constellations. A single family may shift between them depe nding on context, the children’s ages, or even mood. What matters most for educators is:

nding on context, the children’s ages, or even mood. What matters most for educators is:

- Avoid caricatures: Behind every position are deep rationalities that deserve to be heard.

- Find leverage points: The dialectic thinker might connect with the nostalgic; the weary one might find practical alternatives through the guardian.

- Recognize silences: The late navigators are often left out of these debates, deepening their exclusion.

This map isn’t meant to label—it’s meant to shed light on the nuances that make the family-school dialogue about technology both complex and fascinating. Ultimately, it reflects something deeper: our visions of childhood, learning, and the future we imagine.

IMPORTANT: This is not intended to be a “serious” taxonomy or to ‘establish’ a way of viewing the people in a family; it is just an exercise in reflection to continue reflecting with my students and promote their critical thinking

On this ‘cartography’ I will create some task for the students that will promote an empathic and critical exercise of content with the news surrounding us… but I will tell you about that another day, I suppose 😉.

The facilitator is responsible for proactively leading the group, ensuring efficient organisation, clear communication, and a positive working environment. This role involves distributing tasks among group members, ensuring everyone understands their responsibilities, and supervising the completion of work within the established deadlines. Additionally, the facilitator reviews the group’s deliverables to ensure they meet quality standards in content, format, and style. To achieve this, they may use digital tools such as Grammarly or DeepL Write to enhance the precision and professionalism of the texts.

The facilitator is responsible for proactively leading the group, ensuring efficient organisation, clear communication, and a positive working environment. This role involves distributing tasks among group members, ensuring everyone understands their responsibilities, and supervising the completion of work within the established deadlines. Additionally, the facilitator reviews the group’s deliverables to ensure they meet quality standards in content, format, and style. To achieve this, they may use digital tools such as Grammarly or DeepL Write to enhance the precision and professionalism of the texts. The translator is responsible for selecting, each week, four core concepts directly related to the weekly task. These concepts must connect to the task’s content, the type of media produced as part of the task, or the class dynamics used for presenting the task. At least one concept must address the geek component, one must relate to the methodological-pedagogical aspect, and two must focus on the

The translator is responsible for selecting, each week, four core concepts directly related to the weekly task. These concepts must connect to the task’s content, the type of media produced as part of the task, or the class dynamics used for presenting the task. At least one concept must address the geek component, one must relate to the methodological-pedagogical aspect, and two must focus on the  The analyst is responsible for conducting the final reflection of the assignment and evaluating group members’ performance each week. This role requires critical and metacognitive abilities to analyze both individual and collective learning, as well as the dynamics of the group’s teamwork.

The analyst is responsible for conducting the final reflection of the assignment and evaluating group members’ performance each week. This role requires critical and metacognitive abilities to analyze both individual and collective learning, as well as the dynamics of the group’s teamwork. The Star is a key group member responsible for presenting the task, collecting feedback from both the professor (Linda) and peers, and using that feedback to improve the task. This role requires strong communication skills, active listening, and the ability to reflect on and constructively implement feedback.

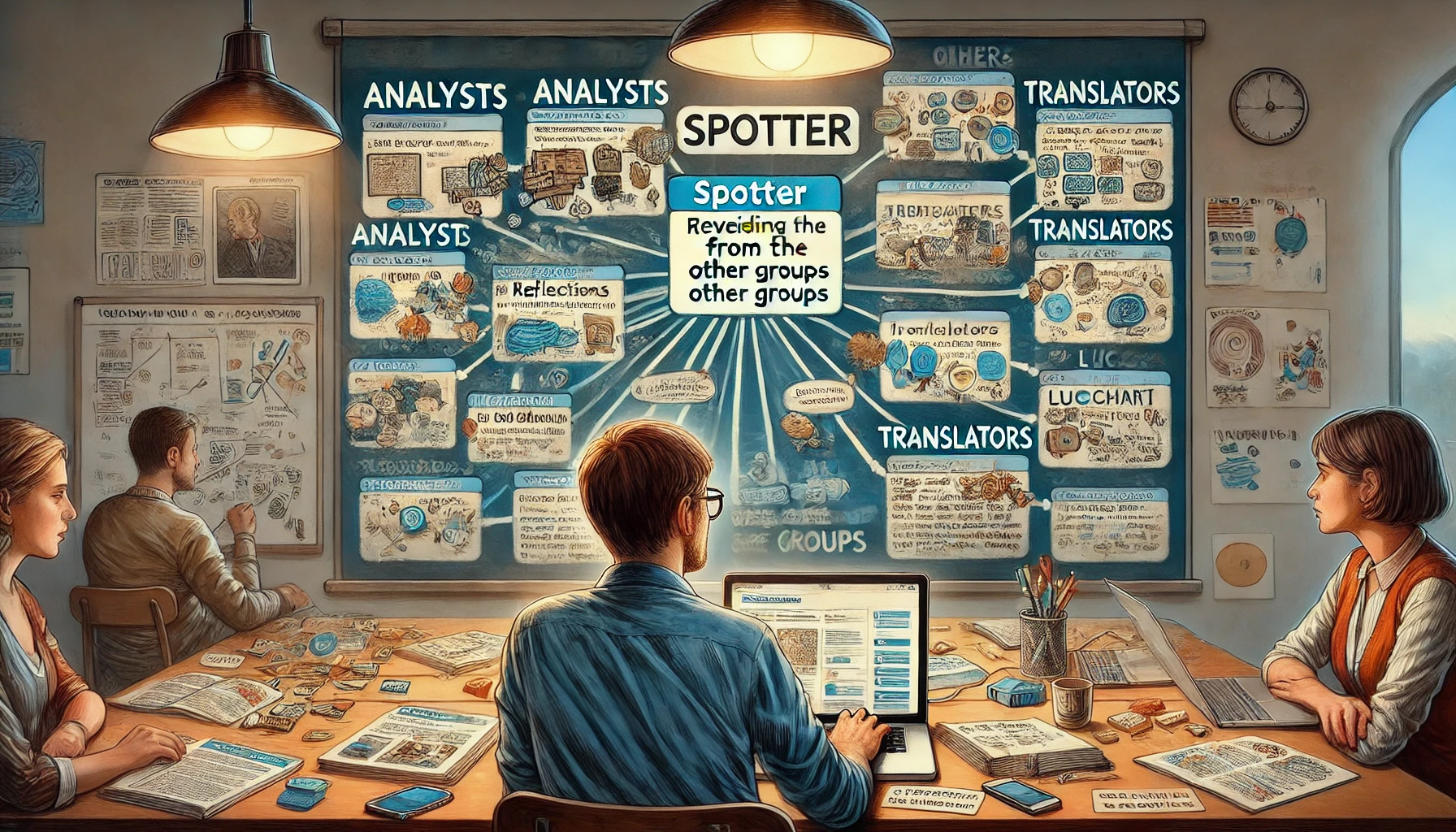

The Star is a key group member responsible for presenting the task, collecting feedback from both the professor (Linda) and peers, and using that feedback to improve the task. This role requires strong communication skills, active listening, and the ability to reflect on and constructively implement feedback. The Spotter is a key member of the group responsible for reviewing the blogs of other groups and analysing the posts of the Analysts and Translators from at least two groups in the class for the PREVIOUS task. Their mission is to identify what their group has not considered, whether concepts, reflections, or approaches, and bring new perspectives to enrich the group’s work.

The Spotter is a key member of the group responsible for reviewing the blogs of other groups and analysing the posts of the Analysts and Translators from at least two groups in the class for the PREVIOUS task. Their mission is to identify what their group has not considered, whether concepts, reflections, or approaches, and bring new perspectives to enrich the group’s work.

than 75 tools and I hope that, having incorporated it into the way they work with technology, it will be useful as a revival of their approach to technology

than 75 tools and I hope that, having incorporated it into the way they work with technology, it will be useful as a revival of their approach to technology

of documenting everything that happens in the group, having the freedom to do his/her task in the format he/she considers most appropriate, and the students are encouraged to “tell the stories” of their groups using the variety of formats allowed by ICT. It is hoped that such a chronicle can serve, in addition to the teacher’s obvious process evaluation purposes, the group as a field notebook and record that will enable them to make decisions about whether to maintain or modify their own internal work dynamics.

of documenting everything that happens in the group, having the freedom to do his/her task in the format he/she considers most appropriate, and the students are encouraged to “tell the stories” of their groups using the variety of formats allowed by ICT. It is hoped that such a chronicle can serve, in addition to the teacher’s obvious process evaluation purposes, the group as a field notebook and record that will enable them to make decisions about whether to maintain or modify their own internal work dynamics. The curator is in charge of compiling and organizing in a schematic way all the sources of information that the group has used for the development of the activity. In addition, he or she must be in charge of sequencing the documentation indicating the process carried out and linking and referencing (according to APA standards) this documentation in a schema (mind map) so that this mechanism allows students to make a representation of a part of the cognitive structure they have set up for the specific task (McKeachie et al., 1987, p. 15).

The curator is in charge of compiling and organizing in a schematic way all the sources of information that the group has used for the development of the activity. In addition, he or she must be in charge of sequencing the documentation indicating the process carried out and linking and referencing (according to APA standards) this documentation in a schema (mind map) so that this mechanism allows students to make a representation of a part of the cognitive structure they have set up for the specific task (McKeachie et al., 1987, p. 15). classified by its function, among those that help students to formulate what they know and to integrate it, as well as those that aim to encourage students’ thinking and improve their reasoning (Johnson et al., 1999).

classified by its function, among those that help students to formulate what they know and to integrate it, as well as those that aim to encourage students’ thinking and improve their reasoning (Johnson et al., 1999). Inspired by the role of Analyst described in some of the works referred to in Strijbos and De Laat (2010), the analyst is the role responsible for making the final reflection of the work and also make the weekly evaluation of the performance of group members.

Inspired by the role of Analyst described in some of the works referred to in Strijbos and De Laat (2010), the analyst is the role responsible for making the final reflection of the work and also make the weekly evaluation of the performance of group members. The role of the star is to present to the whole class the final product of the weekly tasks, attending to the requirements specified by each task.

The role of the star is to present to the whole class the final product of the weekly tasks, attending to the requirements specified by each task.